For the first 15 years of my career, I became a bit of an authority on improving the effectiveness of organisations through total quality management (TQM) and the ‘excellence’ movement. This wasn’t random, it was about teaching lots of people about how to perform simple experiments in their work – some of which were bound to involve failures which was a necessary part of improving overall. Another strand of this was empowering people at all levels in a hierarchy to question and to design experiments to improve aspects of their work. For this to happen, their managers had to create room, breathing space, demonstrate confidence in their people, and build trust two ways. This calls for a transformation in personal beliefs and attitudes among the leaders (especially managers). The next 15 years focused on this leadership transformation through coaching as I felt it was the most critical aspect.

Such a shift is just as important for society.

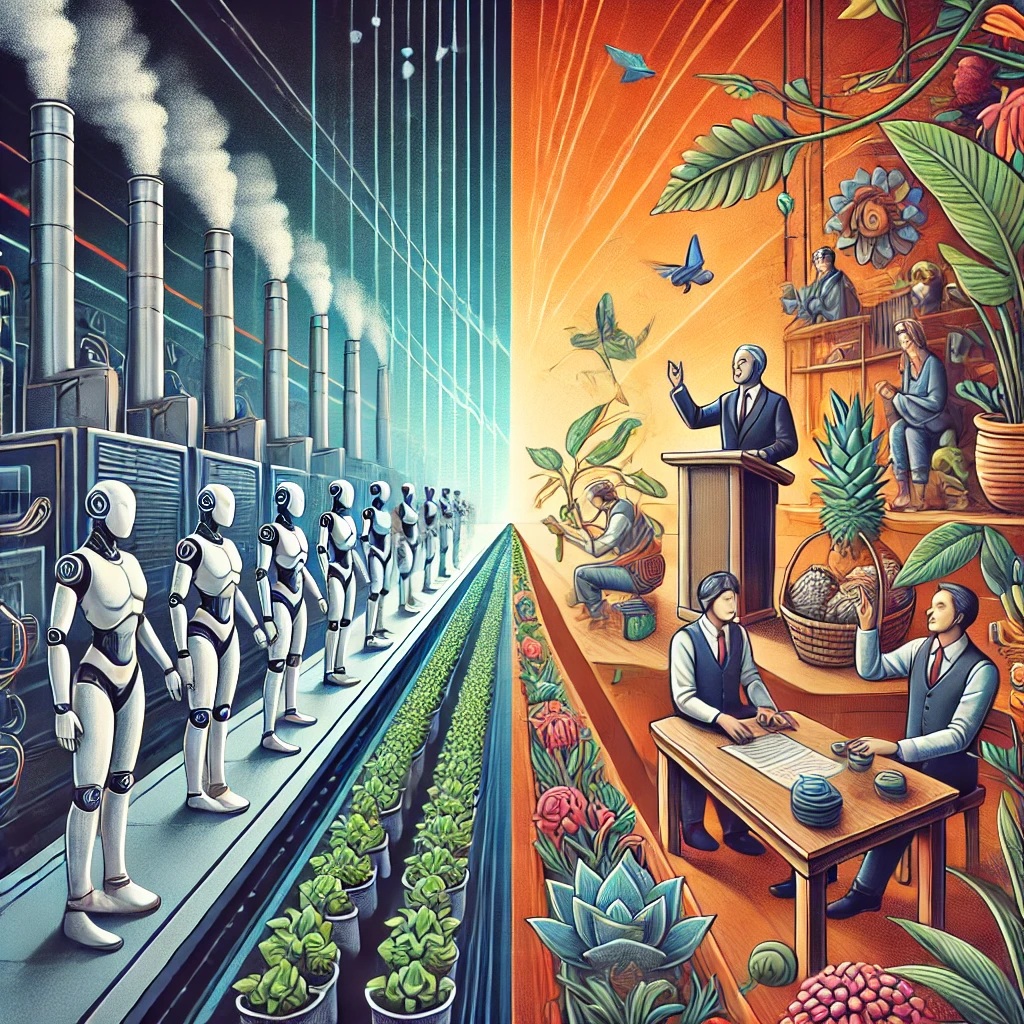

In the last few months, I have heard calls for efficiency improvement from many quarters. Our drive for efficiency, to get more from less, has serious unintended consequences in our lives and the world we live in. While it seeks to maximise output and minimise waste, it can erode creativity, innovation, and well-being. Efficiency is important, but when pursued single-mindedly, it can create rigid systems, stifle critical thinking, and neglect the human aspect of work and life. So let’s explore the downside of efficiency and the positives of inefficiency (what might seem to be indulgence and idleness)…

The Downside of Efficiency

- Erosion of Creativity and Experimentation

Efficiency often demands predictable outcomes and measurable returns. This discourages risk-taking and the trial-and-error processes that are essential for innovation. People fear failure, yet failure often provides critical learning opportunities. Without room for error, learning stalls. - Dehumanisation

Over-efficient systems can treat people as resources rather than individuals. In workplaces, this leads to burnout, stress, and dissatisfaction. Efficiency can prioritise tasks over relationships, reducing opportunities for collaboration and trust-building. - Environmental Costs

In the natural world, efficiency often equates to exploitation. Overproduction and hyper-consumption deplete resources and harm ecosystems. Efficiency rarely accounts for long-term sustainability. - Loss of Depth and Reflection

The constant push for productivity leaves little time for reflection or strategic thinking. Deep work, which requires time and focus, suffers when efficiency prioritises rapid task completion.

The Positives of Inefficiency

- Room for Creativity and Innovation

Inefficiency creates space for play, exploration, and experimentation. These are the seeds of innovation. When people feel free to try new ideas without fear of failure, they are more likely to discover breakthroughs. - Human-Centred Workplaces

Allowing time for inefficiency fosters better relationships, stronger teams, and greater job satisfaction. People feel valued when they have the space to contribute ideas and question norms. - Resilience and Adaptability

Systems built for efficiency are often fragile. Inefficiency allows for redundancy and flexibility, making systems more resilient to shocks. This is as true for organisations as it is for natural ecosystems. - Time for Reflection

Taking time to pause, reflect, and ask bigger questions is often inefficient in the short term but invaluable for long-term success. Reflection helps align actions with values and ensures that we pursue meaningful goals. - Environmental and Social Benefits

A slower pace of life allows for sustainable choices. Inefficiency in resource use often mirrors the cyclical, restorative processes of nature.

A Transformational Leadership Approach

Transforming leadership beliefs is key to fostering the positives of inefficiency. Leaders must unlearn the notion that busyness equals value. Instead, they need to create cultures where experimentation, questioning, and reflection are rewarded. Managers must carve out breathing space for their teams, recognising that meaningful progress often comes from what looks like idleness.

This shift is not just organisational but societal. We must redefine success, prioritising well-being, sustainability, and creativity over relentless productivity. By embracing the “inefficient,” we rediscover the depth and richness of human experience.

The impact of less ‘efficiency’ on national and international economy.

The pursuit of relentless efficiency in national and international economies has reshaped the global landscape, often at a cost to equity, sustainability, and resilience. By contrast, a more balanced approach that embraces less efficiency can deliver significant benefits, not only to individuals and communities but also to economies as a whole. While this may seem counterintuitive, inefficiency fosters long-term growth, stability, and inclusiveness.

National Economic Benefits of Less Efficiency

- Strengthening Local Economies

Prioritising inefficiency at the national level encourages investment in local production and small businesses. Hyper-efficient supply chains often rely on centralisation, just-in-time models, and global sourcing, which undercut local industries. By supporting less efficient but locally based systems, nations can boost domestic employment, improve income equality, and retain wealth within communities. For instance, small-scale farming may appear less efficient than industrial agriculture, but it provides local jobs, enhances food security, and sustains rural economies. - Creating Diverse Job Opportunities

Economies focused on efficiency often favour automation and large-scale industrialisation, reducing the need for human labour. This approach displaces workers and concentrates wealth. Allowing room for less efficient processes—such as artisanal manufacturing or service industries—diversifies the job market and reduces structural unemployment. These roles often provide higher job satisfaction and a sense of purpose, strengthening the social fabric. - Encouraging Innovation

National economies benefit from inefficiency by creating spaces where experimentation can thrive. While efficiency demands immediate returns, inefficiency allows for trial and error, fostering creativity and long-term breakthroughs. Governments that invest in research and development, even with uncertain outcomes, stimulate innovation. These investments can lead to transformative industries, as seen in renewable energy technologies, which initially required subsidies and leniency to compete with fossil fuels. - Building Economic Resilience

Highly efficient systems are often brittle and vulnerable to disruption. For example, lean supply chains proved fragile during the COVID-19 pandemic, leading to global shortages of essential goods. By building redundancy and inefficiency into systems, national economies can better withstand shocks. Resilience through inefficiency—such as maintaining strategic stockpiles or diversifying supply chains—ensures continuity and reduces economic volatility.

International Economic Benefits of Less Efficiency

- Reducing Exploitation

The global race for efficiency often drives exploitation of labour and resources in developing countries. By shifting towards less efficient but fairer production systems, international economies can reduce inequalities. Ethical trade practices, such as fair wages and sustainable resource management, may lower short-term profitability but lead to healthier, more stable economies worldwide. This, in turn, increases global consumer spending power, benefiting all nations. - Promoting Sustainability

Efficiency in global markets prioritises speed and cost-cutting, often at the expense of environmental sustainability. By allowing inefficiencies—such as slower, more sustainable production and transport methods—countries can reduce greenhouse gas emissions, preserve biodiversity, and combat climate change. The European Union’s push for a circular economy exemplifies how inefficiency can promote environmental health, with long-term benefits for all trading partners. - Fostering Global Collaboration

Less efficient systems encourage slower, more deliberate approaches to international cooperation. Rushed decision-making, driven by the desire for efficiency, often overlooks the nuances of global challenges. By prioritising inclusive, consensus-driven processes, international bodies like the United Nations can achieve solutions that are more equitable and enduring. For example, the Paris Agreement’s collaborative nature reflects how less efficient processes can yield globally beneficial outcomes. - Mitigating Economic Inequality

Efficiency in global economies has concentrated wealth in a few nations and corporations. Less efficient practices—such as rebalancing trade policies, supporting developing economies with fair trade agreements, and investing in global infrastructure—can distribute economic benefits more equitably. This fosters global stability, as nations with greater economic equity are less likely to experience political unrest or conflict.

The Bigger Picture

Moving away from hyper-efficiency does not mean embracing chaos or wastefulness. Instead, it reflects a more balanced approach that prioritises sustainability, inclusiveness, and resilience. National and international economies that recognise the value of inefficiency can create systems that are more equitable, innovative, and robust. In an interconnected world, the benefits of these shifts ripple outward, improving lives and safeguarding the planet for future generations.

Inefficiency, employment, the working week, and intrinsic motivation

Less emphasis on efficiency can profoundly transform employment, the working week, and intrinsic motivation, creating more humane and sustainable economies.

Employment

Efficiency often prioritises automation and cost-cutting, displacing workers and eroding job security. By valuing less efficient practices, economies can support labour-intensive industries that foster local employment, such as artisanal manufacturing, community-based services, or regenerative agriculture. These roles often involve meaningful work that connects individuals to their communities. Moreover, less efficient systems allow organisations to prioritise quality over quantity, creating jobs that require creativity, craftsmanship, and human connection—qualities automation struggles to replicate.

The Working Week

The drive for efficiency has normalised long hours and overwork, leading to burnout and diminished productivity. Reducing working hours—while seemingly inefficient—can improve overall well-being and output. Studies show that shorter workweeks, such as four-day schedules, enhance productivity by allowing employees to rest and recharge. This approach fosters better focus, creativity, and engagement. Countries like Iceland and New Zealand have piloted reduced workweeks with great success, showing that less efficiency in scheduling leads to more sustainable performance.

Intrinsic Motivation

Hyper-efficient systems often undermine intrinsic motivation by focusing on external pressures like quotas or targets. This reduces autonomy, mastery, and purpose—key drivers of motivation. When less efficient processes allow employees to explore, experiment, and engage deeply with their tasks, they feel greater ownership and pride in their work. Managers who encourage such practices create environments where workers are not just task-doers but active participants in innovation and improvement, fostering intrinsic satisfaction and long-term engagement.

Politics and efficiency/inefficiency ‘debate’

The politics of efficiency versus inefficiency reflects deep ideological divides and competing visions for society. Advocates of efficiency often align with market-driven, neoliberal politics (UK: Conservatives / US: Republicans). They prioritise streamlined processes, cost-cutting, and measurable outcomes. This approach seeks to maximise returns on investment, reduce public spending, and foster competitiveness. Proponents argue that efficiency drives economic growth, lowers taxes, and makes governments accountable by delivering results.

In contrast, those sceptical of efficiency often adopt more progressive or social-democratic views (UK: Labour / Greens). They argue that efficiency can overlook equity, sustainability, and the human cost. Public services, for instance, may become “efficient” by cutting staff or reducing access, leading to poorer outcomes for vulnerable populations. Critics highlight that inefficiency allows space for care, creativity, and democracy—values difficult to quantify but essential for societal well-being.

The debate is particularly contentious in areas like healthcare, education, and welfare. Efficiency advocates favour privatisation and performance metrics, while opponents stress that these sectors thrive on trust, relationships, and flexibility. Internationally, efficiency-oriented trade deals and supply chains often exacerbate inequalities, while proponents of “inefficiency” favour fair trade and environmental protections.

Ultimately, this debate reflects political choices about what societies value: short-term gains or long-term sustainability, measurable results or intangible benefits, and growth or equity.